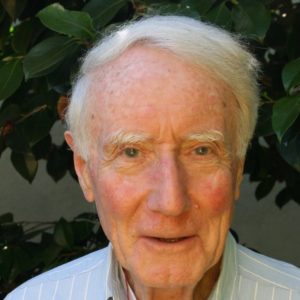

From the American Exception Editors:

We have embedded two related episodes of the American Exception podcast above. They feature Peter Dale Scott, Aaron Good, Alfred McCoy, and Ben Howard. Special Thanks to Seamus McGuinness for his work on this project!

Old Wealth, the Kuomintang, and Air America:

How the CIA Impounded an Essay of Mine in 1970

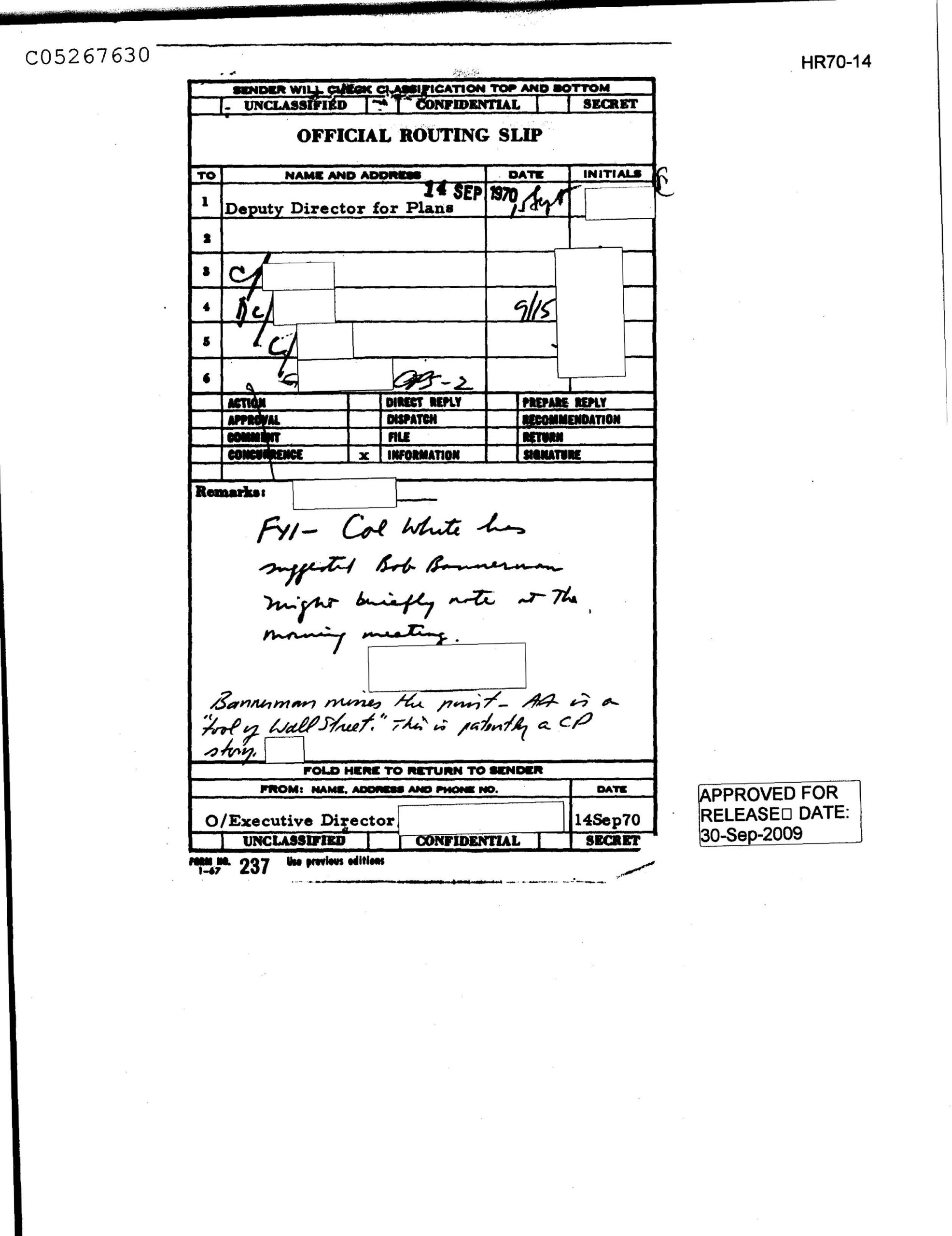

I remember nothing about this essay. CIA notations suggest I that submitted it to Ramparts magazine in September of 1970. However, a cover sheet indicates very clearly that the article was entered into CIA records on August 18, 1970. The article was never published before now, and I have no way of knowing whether it ever reached Ramparts or not.1

It was, however, passed from the CIA’s Deputy Directorate of Security to the Office of the Executive Director/Comptroller, Col. Lawrence K. White, who in September forwarded it to the Deputy Director of Plans for brief discussion “at the morning meeting.”2

The year 1970 was a busy one for me. Earlier that year, I had three anti-war articles published in the New York Review of Books and two more in Ramparts. In June, I submitted to Bobbs Merrill the manuscript of my book, The War Conspiracy, which was not published until two years later in June of 1972. By then, the book contained an additional chapter, on “Opium, the China Lobby, and the CIA,” which incorporated some of the prose from this lost August 1970 essay.

By June of 1970, someone in the CIA was aware of me, because I consented to the request of a fellow researcher, a CIA veteran, that I let the CIA look at my book manuscript. He told me later that a car drove over from San Francisco to Berkeley, to pick it up from him.

Reading the essay a half century later, I see an argument in it that I would not endorse: the suggestion that the socially prominent New Yorkers on the boards of CIA proprietary firms had any control over those firms, rather than merely serving as a front for the agency. However, I do believe that article demonstrated two important facts about the early CIA: (1) how enmeshed the agency was in both policies and personnel with New York inherited wealth, and (2) how the early policies of that milieu were determined by private interests, sometimes in direct conflict with public objectives.

Today we have further evidence in support of the second proposition.

The date of 1970 explains certain glaring omissions in the essay. I could not then have been aware of the impending close to the era of eastern US establishment-Kuomintang cooperation, as Nixon, starting with the “ping pong diplomacy” of 1971, began the delicate task of nudging America towards the major policy change of recognizing Communist China.

Nor could I have foreseen the extent to which Nixon would realign the base of the Republican Party, exploiting white racist resentment in the South, and thus wresting control of the party away from white establishment liberals in the northeast. That realignment culminated in the Reagan Revolution of 1981. It was accompanied by the creation of a new organization called the Council on National Policy, explicitly designed by people like the rich Texan Nelson Bunker Hunt to combat the influence of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

But the biggest omission reflects how little I knew then about the postwar development of US support for Kuomintang remnant troops in Burma. A key role in this was played by Paul Helliwell—a Miami lawyer and a veteran of the OSS in Kunming. Helliwell acted first in his role in the Far East Division of the Strategic Service Unit (1945-47), a successor to OSS. Later he was instrumental in the creation of two CIA proprietary companies: SEA Supply Inc, and CAT—the latter of which became Air America. SEA Supply and CAT Inc. were both incorporated by Helliwell as a Miami lawyer for Frank Wisner’s Office of Policy Coordination (OPC).

This direct US support for the chief opium traffickers of the Southeast Asian “Golden Triangle” became official with Truman’s authorization in late 1950 of Operation Paper. This CIA/OPC program—which CIA Director Walter Bedell Smith, a Midwesterner, had opposed—was intended to divert Chinese armed forces towards their southern frontier, away from the conflict in Korea.

A key role in this support to Kuomintang remnants had been played earlier by a private Thai trading company set up in 1946 by Willis Bird, a veteran of OSS China under Helliwell. After mishandling a post-war mission to Korea, Bird had left OSS under a cloud, but remained a friend of OSS Chief William Donovan. Bird’s trading company is said to have been originally financed by his friend Donovan’s post-war World Commerce Corporation (WCC), and Donovan himself visited Thailand in 1948. William Stevenson writes specifically that Donovan “turned Siam into a base from which to run [postwar] secret operations against the new Soviet threat in Asia.”3

I should have written more about the WCC in my 1970 essay, for reasons that will become clear later in this introduction.

With Truman’s approval of the KMT-supporting Operation Paper in 1950, Bird’s trading business was subsumed under the new CIA proprietary that Bird’s old boss Helliwell had incorporated in Miami, SEA Supply, Inc. But Bird himself was now well established in right-wing, anti-democratic, Thai military circles. He even plotted secretly with them to prepare for a Thai military coup in 1950—against, and sometimes in overt opposition to, the US Embassy’s efforts to consolidate Thailand’s fragile democracy. The 1950 coup brought to power Phao Sriyanon, the Thai general controlling the movement of KMT opium through Thailand from the rebel Shan states in Burma. It was not long before Phao was alleged to be the richest man in the world.

As I write in American War Machine,

Bird’s energetic promotion of Phao, precisely when the U.S. embassy was trying to reduce Phao’s corrupt influence, led to a 1951 embassy memorandum of protest to Washington about Bird’s activities. “Why is this man Bird allowed to deal with the Police Chief [Phao]?” the memo asked.4

But the uncontrollable Bird, in his de facto consolidation of the opium traffic in Thailand, appears to have conformed to the purposes of an unseen higher force which overrode the policy of the appointed officials in the U.S. Embassy. What Bird did was in concert with Helliwell in Miami, as well as with Helliwell’s CIA proprietaries, SEA Supply and CAT/Air America. Additionally, the Thai Border Patrol Police (BPP), part of General Phao’s military forces, had been receiving covert U.S. intelligence support, training, and military aid, from as early as 1948 following their role in an earlier Thai military coup in 1947.

Bird’s collusion with a major drug trafficker was in concert with other CIA-related activities at this time in remote areas, from France, Italy, and the Middle East, to Mexico and Taiwan. In later years, similar operations would be carried out in Chile, Colombia, Venezuela, Australia, and Afghanistan.5

These widely dispersed grey alliances with drug traffickers were interconnected but from a base outside the United States. Starting in 1950, Ting Tsuo-shou, civilian advisor to the KMT troops in Burma, began organizing for a larger Anti-Communist League.6 In 1954, ostensibly as part of the CIA operation to overthrow the Arbenz government of Guatemala, Howard Hunt (the future Watergate plotter), helped organize a Latin-American chapter for the League.7 In the same year, the Asian Peoples’ Anti-Communist League (APACL) was established in Taiwan, allegedly with financial support from the CIA Deputy Chief of Station there, Ray Cline.8

In 1950, the Kuomintang ambition of “rolling back” Communism in Asia was endorsed by both the Republican Party and General Macarthur at his SCAP Headquarters in Japan. But it was opposed by the containment policy devised by Truman, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, and George Kennan.

Truman and Acheson had even worse news for the KMT, now re-established in Taiwan. “In January 1950, [they] publicly announced that Washington would not provide military assistance to safeguard Taiwan.”9

That Taiwan and the KMT survived was due largely to private initiatives taken by Admiral Charles M. Cooke, former commander of the US Seventh Fleet. In February 1950, Cooke flew to Taiwan, on a trip “apparently arranged by SCAP headquarters with MacArthur’s approval [while] the State Department and the U.S. Embassy in Taipei were kept in the dark.”10

A month later,

Cooke worked out a draft contract, in which he proposed the formation of a “Special Technician Program” (STP) under the nominal supervision of the New York–based Commerce International China Inc. (CIC), a subsidiary of World Commerce Corporation chaired by S. G. Fassoulis, another powerful figure in the China lobby…. The CIC’s complex pedigree thus imbued the STP with political intrigue from its inception. As Cooke admitted later in a congressional hearing in October 1951, he never received any governmental authorization for the STP, nor for any of the several related underground activities undertaken through these ostensibly commercial firms.11

In the same month of March, Cooke and the WCC affiliate Commerce International (China) began purchasing millions of dollars of munitions for Taiwan. Rumors that they would purchase 426 surplus tanks in the Philippines,

…disturbed politicians at both the U.S. State Department and the British Foreign Office, who worried that these heavy weapons would eventually fall to the Chinese Communists when Taiwan was captured, thus posing a threat to the West.12

Some of Cooke’s backers in the World Commerce Corporation had personal as well as ideological reasons for covertly opposing the Truman-Acheson Taiwan policy. These backers included wealthy oligarchs from both America (Nelson Rockefeller, John J. McCloy, Richard Mellon, and David Bruce) and Britain (Sir Victor Sassoon and Sir William “Tony” Keswick).13

In this list, it is relevant that Richard Mellon and David Bruce (his cousin by marriage) were both directors of Pan Am, which Bruce had helped bring into being. Sir Victor Sassoon had been a major pre-war investor in Shanghai, where the chief British interests were represented by the trading company Jardine Matheson—headed by Sir William Keswick, a collateral descendant of the Jardine family, and a director of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank.14 All would gain considerably if the KMT could reestablish itself in mainline China.

Hsiao-ting Lin’s well-researched book, published by Harvard University Press, argues emphatically:

With the advisory assistance of the retired former commander of the Seventh Fleet, Admiral Charles M. Cooke, and his “Special Technician Program” in Taiwan, Chiang Kaishek was able to withstand a critical stage of his political career in the months surrounding the outbreak of the Korean War.15

So we see that in Taiwan with Cooke, just as in Thailand with Willis Bird, Americans backed by the World Commerce Corporation were able to further the interests of the Kuomintang, against the policies of Truman and his administration.

Others have argued that the World Commerce Corporation, perhaps with access to Nazi gold in Austria, played a similar role in preserving the cadres of OSS through the difficult 1945-1947 years, after OSS was dissolved by Truman and before the CIA was created. All in all, between 1945 and Eisenhower’s 1953 inauguration, we see two historically important trends. First, we see how private wealth—consolidated in the World Commerce Corporation—pursued policies which diverged with those of the public state. Secondly, in the matters we have discussed, the World Commerce Corporation prevailed over the public state.16

That is, I believe, the core story underlying my 1979 essay.

Peter Dale Scott

Berkeley, California

June 2, 2022

FOOTNOTES:

1. The Wikipedia article on Operation CHAOS lists Ramparts as one of five “targets of Operation CHAOS within the antiwar movement.” However CHAOS was a Counterintelligence operation. My essay appears to have been collected by “Project Two,” the CIA’s Office of Security’s parallel surveillance operation. The file number on the fully redacted CIA page, (DD/S 3717) is for an OS file from 1970, perhaps mine.

2. Two marginal queries on the second page of my MS suggest that a senior CIA officer may not have been aware of the facts I was reporting, including the very relevant one that some Air America planes, despite being funded through a CIA proprietary, were not fully under CIA control.

3. William Stevenson, The Revolutionary King, 50-51; quoted in Peter Dale Scott, The American War Machine, 72. Cf. William O. Walker III, Opium and Foreign Policy: The Anglo-American Search for Order in Asia, 1912-1954 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 184-85:

[By 1947] The United States increasingly defined for Thailand a place in Western strategic policy in the early cold war. Among those who kept close watch over events were William J. Donovan, wartime head of the OSS, and Willis H. Bird, who worked with the OSS in China…. After the war, Bird,… still a reserve colonel in military intelligence, ran an import-export house in Bangkok. Following the November [1947 Thailand coup] Bird…implored Donovan: “Should there be any agency that is trying to take the place of O.S.S.,… please have them get in touch with us as soon as possible. By the time Phibun returned as Prime Minister, Donovan was telling the Pentagon and the State Department that Bird was a reliable source whose information about growing Soviet activities in Thailand were credible.

4. Peter Dale Scott, American War Machine: Deep Politics, the CIA Global Drug Connection, and the Road to Afghanistan (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 83; citing Foreign Relations of the United States, 1951, Vol. 6, Pt. 2, 1634. The memo described Bird as “the character who handed over a lot of [US] military equipment to the Police, without any authorization as far as I can determine, and whose status with CAS [local CIA] is ambiguous, to say the least.”

5. In the 1990s, Dennis Dayle, a retired senior DEA official, said on camera in my presence that “In my 30-year history in the Drug Enforcement Administration and related agencies, the major targets of my investigations almost invariably turned out to be working for the CIA.” (Peter Dale Scott, American War Machine, 149); Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall, Cocaine Politics (1998 edition), xviii-xix).

6. Bertil Lintner, Burma in Revolt, 111–14.

7. Peter Dale Scott, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK, 109. The Conference convened to cement this alliance was chaired by Antonio Valladares, the Nicaraguan lawyer for New Orleans mobster Carlos Marcello.

8. Scott Anderson and Jon Lee Anderson, Inside the League, 54-55; cited in Jonathan Marshall, Peter Dale Scott, and Jane Hunter, The Iran-Contra Connection, 65. In 1967 the APACL became part of a larger World Anti-Communist League (WACL). According to Wikipedia, Both Hunt and Cline were stationed by OSS in China, where in 1946 they collaborated with OSS Kunming Chief Paul Helliwell (“Ray S. Cline,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ray_S._Cline#Early_life_and_family). I have not been able to confirm this. I learned much by studying the American delegations to the annual conferences of the APACL, which included the names of young people from American who later became noteworthy for other reasons. Let me cite in particular:

- Spas T. Raikin, the Secretary-General of the American Friends of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations., who is named in the Warren Report (p. 718) as the “representative of the Traveler’s Aid Society” who met Lee and Marina when they landed in Hoboken after their voyage from Russia in 1962;

- Tom Huston, later briefly famous as the nominal author of the “notorious Huston Plan” of 1970 “for expansive surveillance of domestic protest movements during the Nixon presidency” (“Spying on Americans: Infamous 1970s White House Plan for Protest Surveillance Released,” National Security Archive, June 25, 2020, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/intelligence/2020-06-25/spying-americans-new-release-infamous-huston-plan);

- Douglas Caddy, later briefly famous as the first attorney for the seven men arrested for the 1972 Watergate burglaries.

9. Hsiao-ting Lin, The Accidental State: Chiang Kai-shek, the United States, and the Making of Taiwan [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016]. 141). Earlier, in March 1949, “the White House adopted NSDC 34/2, in which it declared its desire to maintain contact with the CCP [Chinese Communist Party]. In so doing, it hoped to draw the Chinese communists away from the Soviet Union” (Victor S. Kaufman, “The United States, Britain and the CAT Controversy,” Journal of Contemporary History, 40:1, January 1, 2005, 96).

10. Lin, The Accidental State, 144: “They were told that the purpose of [the] visit to Taiwan was to conduct private business, including ‘selling fertilizer’.” I presented a version of the Cooke-Fassoulis story in The War Conspiracy (279), adding the detail, not reported by Lin, that “Fassoulis, accused of passing bribes as the vice president of Commerce International, was under indictment ten years later when he surfaced in the syndicate-linked Guterma scandals.” Such collaboration between overworld and underworld is not infrequent, leading me to write on occasion of “The Dark Quadrant” (Peter Dale Scott, Crime and Cover-Up, 46).

11. Lin, The Accidental State, 145-46. The STP proposal was implemented by Cooke, but not initiated by him. In November 1949, a proposal for such a technician mission had been proposed in a letter to Acheson by William Pawley, who before the war had been President of Pan Am’s Chinese Affiliate CNAC, and who was in business after the war with WCC director John J. McCloy. Pawley

asked for “approval or acquiescence” of private American citizens going to Taiwan, if their civil services wee contracted directly by the Nationalist government and if the United States took no part therein. Although Acheson gave Pawley the “acquiescence” he requested, nothing substantial followed (Lin, The Accidental State, 141-42).

At the same time Pawley participated in the elaborate legal scheme devised by Donovan and OPC to transfer ownership of China’s civil air fleet (including CNAC planes) from Chinese government ownership to an ad hoc Delaware corporation owned by Claire Chennault and his partner Whiting Willauer (Alfred T. Cox, “Civil Air Transport (CAT): A Proprietary Airline 1946-1955,” CIA, Clandestine Services, Historical Paper, April 1967, I, 95ss, https://archive.org/stream/CivilAirTransport/Clandestine%20Services%20History%20-%20Civil%20Air%20Transport%20%28CAT%29%20A%20Proprietary%20Airline%201946-1955%20Volume%201_djvu.txt).

12. Hsiao-ting Lin, “Taiwan’s Secret Ally,” Hoover Digest, 2012 No. 2, April 6, 2012, https://www.hoover.org/research/taiwans-secret-ally/’ cf. Lin, The Accidental State, 148.

13. The Australian scholar Greg Poulgrain has written that the Rockefeller family controlled the Dutch firm Nederlandsche Nieuw Guinea Petroleum Maatschappij (NNGPM), which in the 1930s discovered in New Guinea what may be the world’s largest and most profitable copper and gold mine, and for decades took conspiratorial steps to conceal the scope of this discovery. After the bloody Indonesian coup and massacre of 1965, the new Indonesian dictator, Col. Suharto, signed an agreement for the mine’s development with Freeport Indonesia, where the Rockefellers also had an interest and sat on the board. See Greg Poulgrain, JFK vs. Dulles, 19-20, 23. I am very impressed by Poulgrain’s life-long research into the Asian part of the story, but I have issues with his claims about the American part.

14. The fortunes of the Sassoon family and of the Keswick family both derived from the major trafficking of opium through Shanghai (and Jardine Matheson) in the 19th century, when (at least in the eyes of British law) it was still legal.

15. Lin, The Accidental State, 8.

16. E.g. John Loftus and Mark Aarons, The Secret War Against the Jews, 110-11: “The money for the opiates would eventually come from Nazi gold that had been laundered and manipulated by [Allen] Dulles and [Sir William] Stephenson through the World Commerce Corporation.” Cf. Scott, American War Machine, 72: “Helliwell acquired a banking partner in Florida, E.P. Barry, who had been the postwar head of OSS Counterintelligence (X-2) in Vienna, which oversaw the recovery of SS gold in Operation Safehaven. And it is not questioned that in December 1947 the NSC created a Special Procedures Group “that, among other things, laundered over $10 million in captured Axis funds to influence the [Italian] election [of 1948].” Note that this authorization was before NSC 10/2 of June 18, 1948, first funded covert operations under what soon became OPC.”

Private War Enterprise in Asia:

Air America, the Brook Club, and the Kuomintang

(Original manuscript submitted to Ramparts magazine in September 1970)

It is common practice to speak of the U.S. involvement in Indochina as a chaotic muddle into which America stumbled, as Richard Goodwin has put it, “almost by accident.” A chief source for this soothing notion has been those who were once in the White House under President Kennedy, and who, understandably, have been quick to tell us that an Asian ground war was never what they intended.

Yet the patterns underlying the confusion are, when studied more closely, all too prevalent: America has not “blundered” erratically forwards like one who is drunk or absent-minded, but has inched inexorably down a road which many observers could foresee. At the end of that road, of course, is an ultimate confrontation with either China, the Soviet Union, or both countries together.

To speak of a society’s designs or intentions is I think a false metaphor; but in our pluralistic society there have been for two decades powerful individuals whose explicit design was just such an ultimate confrontation. Many more have accepted it as a risk worth running for a U.S. presence in Asia. Few of the former have held high office, and some of the most prominent have not held public office at all.

Private Activists and Covert War in Indochina

Within the government, proposals for “rolling back” Communism on the Chinese mainland have come chiefly from dissident minorities in the CIA — men like Chiang Ching-kuo’s close personal friend Ray Cline, who was in effect “exiled” to a quiet post in Germany after proposing a Chinese Bay of Pigs operation in 1962. For years the cause of rollback has been advocated more energetically by General Claire Chennault and Admiral Felix Stump, the Board Chairmen of the “private” airline CAT Inc., since March 31, 1959, known as Air America.

For two decades these private activists have been working to break down governmental inertia. No one of their successes in this campaign has been spectacular. Cumulatively, however, they have landed us in the third largest war of America’s history.

One clear recurrent pattern in Southeast Asia has been the continuous provocations by the CIA and/or CAT/Air America, from the flying of Kuomintang guerrillas into Burma in 1951 to the recent training of Khmer Serai guerrillas and the defoliation of Cambodian rubber plantations, two major factors in the successful overthrow of Prince Sihanouk.

Roger Hilsman, citing the CIA’s “fiascoes” in Indochina, Burma, and Laos, admitted that by 1961 there was a recurring “problem of CIA,” a problem which — from the three examples he cited — might equally well be labeled “the problem of Air America.” Hilsman suggests that the problem was one of inadequate control, just as Schlesinger criticizes the actions in Laos of irresponsible CIA agents “in the field.”

But the CIA continues to have as large a responsibility as ever for our billion-dollar covert war in Laos. Still more surprising, air support for this and other covert activities in Asia continues to be supplied by Air America, a “private” and hence uncontrollable airline whose capital, as we shall show, is derived in large part from Kuomintang sources in Taiwan.

The Problem of Air America

Worse still, though it is commonly hinted in the U.S. press that the CIA “uses” the KMT-linked Air America, I shall argue that the truth is at least as much the opposite way around. Air America is a powerful agent for an expanded war in Asia precisely because it is private, and hence not responsive to Congressional or even Presidential control. Its power, at least until recently, has been derived from that of its financial backers: a strange coalition of KMT wealth in Taiwan and the inherited Wall Street wealth of Manhattan bankers to be found in the New York Social Register.1 In 2022 I would still point to the role of KMT wealth in determining Air America policy. The problem on the American side, I would now say, was in fact not “inherited Wall Street wealth,” but the lack of USG control, perhaps designed for the sake of “plausible deniability.”

Air America is admittedly a marginal instrument in the present expanded Indochina war; yet it has been from the margins, the covert operations in inaccessible places like Laos and Cambodia, that escalations have proven likely to arise. In Nixon’s projected “low profile” for U.S. actions in Asia, the role of the “private” airline will almost certainly increase; and today Air America is indeed taking steps to increase its roster of pilots.

The important point is that Air America’s “privateness” does not make it remote from the sources of power in this capitalistic society; it makes it close to them. And Washington’s desire for peace in Asia will not have been demonstrated until such time as it ceases its contracts with an airline over which it is convenient to have no control.

For example, it is true that, in January 1970, Nixon terminated the unmanned “drone” reconnaissance overflights which had been secretly resumed in October 1969 by the intelligence community, a few days after Ray Cline’s return from Germany.

Yet this constructive step is more than nullified by the actions reported on April 13, 1970 in the Dallas Morning News:

American pilots working with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) are making low-level, night-time flights over Communist China to further dissension and eventual revolution, the Dallas News has been told by a former government flier. “Our boys are doing quite a bit of flying into China,” said John Wiren in an interview.

“They fly upriver at night in old PBY’s [Patrol Bombers]. They drop [Chinese Nationalist] guerrillas and supplies put in there to stir things up.” Wiren… who spent much of the 1960’s flying for the CIA-sponsored airline “Air America” in Laos… said the clandestine flights are made into China as part of a long-range strategic plan. “The big plan is for revolution in China,” he said.

Joe Alsop: A Manufacturer of Crises

Today the excesses of Indochina, and particularly of America’s recent Cambodian adventure, may well have weakened the status of those in America who still harbor such fantasies. It can however be shown that, in the genesis of the Second Indochina War, such individuals, even though “private” rather than “public,” played a role that was central, carefully deliberate, and recurrent.

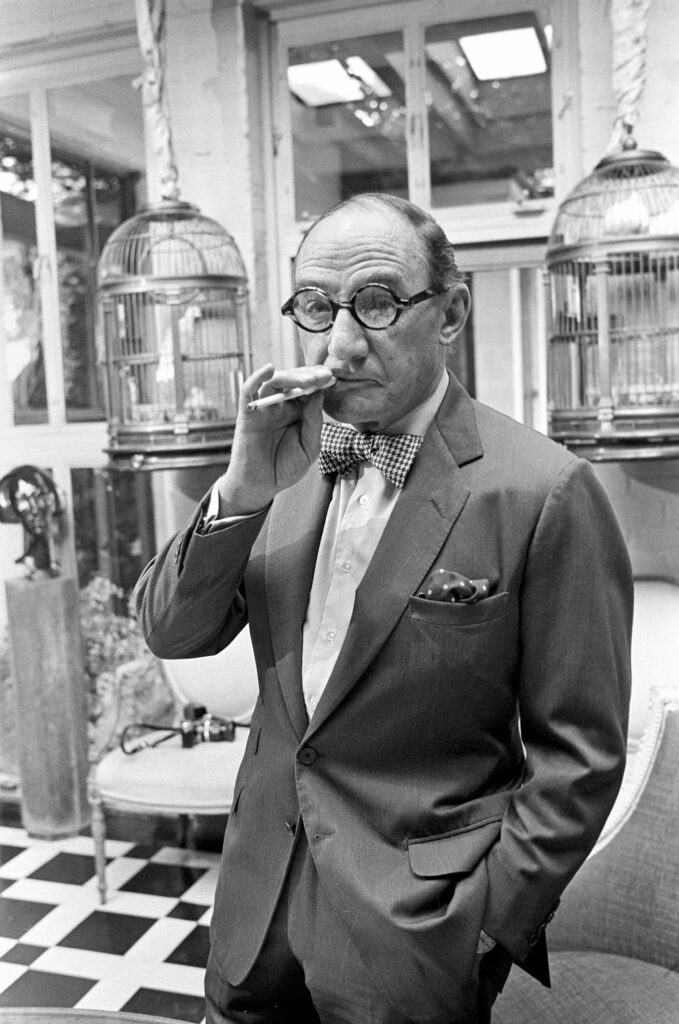

Take for example Joe Alsop, the man who in the not wholly playful words of Townsend Hoopes, “seemed at times to have invented the Vietnam War.”2Hoopes, The Limits of Intervention, 149. “Unexpected” crises in Indochina are not infrequently preceded by Joe Alsop’s ominous visits. The last was to Vietnam in April of this year, when he wrote from Saigon to attack “the possibility that havering and wavering in Washington can cause us to lose the golden opportunity in Cambodia,” to pacify at least half of South Vietnam.3Alsop, Washington Post, Apr. 26, 1970, A23. This column of Alsop’s appeared the day that the National Security Council was scheduled to discuss Cambodian proposals from the Special Action Group that had been convened on April 22, and four days before the intervention was finally approved. A column by Evans and Novak on the same day, written from Phnom Penh, also spoke of a “golden opportunity.”

Joseph Alsop in 1974. Source: New York Times

This timely visit recalls others. Alsop visited Taiwan and Indochina in late 1953, as the French were making their fateful buildup at Dien Bien Phu; he was the first to report USAF support for Dienbienphu before announcing his conversion to Chiang’s and Macarthur’s view that “there was no substitute for victory” in Asia.4Alsop, Washington Post, June, 1954; reprinted in Congressional Record Appendix, June 14, 1954, A4366. Cf. Alsop’s report (Washington Post, Nov. 2, 1953, 8) of an interview with Chiang Kai-shek: “‘If the United States remains on the defensive in Asia for another two years, it will be needless to talk about Free China being in danger, for the U.S. and the whole free world will then be in deadly danger.’ It must be added that every fact of the situation in Asia appears to support and confirm this grim forecast by the Generalissimo.”

He visited Laos and Vietnam in April 1961, in time to witness “Operation Noel,” the first U.S.-advised paratroop operation in Indochina (with transports piloted by Nationalist Chinese and/or American pilots of Air America)5Alsop, Washington Post, Apr. 6, 1961, A9; Apr. 7, 1961, A8, A17. and to “discover” a colonel in Vietnam’s Kien Hoa Province named Pham Ngoc Thao, who for the next two years was primed by an activist CIA faction as a candidate to displace the increasingly untrustworthy Ngo Dinh Nhu.

This Alsop visit preceded by one month the fateful tour in May 1961 of Vice-President Johnson, which led in turn to Kennedy’s Vietnam commitments. In May 1964, finally, Alsop returned to Indochina and advocated the bombing of North Vietnam, on the eve of the June 1 Honolulu Conference which in turn preceded the Tonkin Gulf Incidents.6Alsop, Washington Post, May 22, 1964, A19.

CAT was the logistical backbone for the new post-Korean formula to stop Communism in Asia. As Eisenhower put it, “If there must be a war there, let it be Asians against Asians, with our support on the side of freedom.”

But the most productive of Alsop’s visits was undoubtedly that of August-September 1959, when, as we saw in an earlier issue of Ramparts,7Ramparts, Vol. 8 no. 8, February 1970. America’s covert war in Indochina can be said to have begun. On that occasion two cargo planes of the Taiwan commercial airline Civil Air Transport (i.e. two Air America planes) arrived in Vientiane on August 22, four days before an emergency aid program to pay for them was signed in Washington on August 26, and a week before “proof” of an August 30 North Vietnamese invasion was first brought forward.

Written “En Route to Vientiane,” Joe Alsop’s column of August 26 predicted “that the key city of Sam Neua will soon turn into another Dienbienphu,” an absurd charge that was nonetheless echoed almost immediately by the CIA’s protege General Phoumi Nosavan and by the U.S. press. Alsop arrived barely in time to interview the pretended survivors of a non-existent North Vietnamese “invasion” on August 30; his alarmist report of September 2 contributed to a secret U.S. Executive Order of September 4, under which, among other things, the first U.S. ground troops (an Army Signal unit) were apparently dispatched to “neutral” Laos.8Alsop, Washington Post, Sept. 10, 1959, A9; London Times, Sept. 11, 1959, 12. An official DOD spokesman said only that a signal corps unit had been assigned to Admiral Felt, CINCPAC, for use “in that area” as he saw fit. However, the Bangkok Post reported the next day that the unit “actually was en route to Laos.”

Secret Orders Adopted in Eisenhower’s Absence

Denis Warner, another anti-Communist reporter, heard the same “survivors” as Alsop and was contemptuous: “General Amkha accepted as fact what the most junior Western staff officer would have rejected as fiction”9Warner, The Last Confucian, 210. Bernard Fall goes further and suggests that the evidence was not only false but deliberately staged. But those who swallowed the bait included not only Joe Alsop, who as Warner must have known had been a U.S. staff officer under Chennault in China during the war, but Alsop’s willing believers in Washington who dispatched the undisclosed secret order of September 4.

Apparently, the latter did not include President Eisenhower, who on the crucial day of September 4 was isolated on a one-day golfing holiday at the secluded Culzean Castle in Scotland.

The full content of the secret order is unknown (a later column by Alsop is our only source), but may well have authorized the immediate recruiting of pilots by the “American Fliers for Laos,” a “volunteer” group “said to be negotiating with the Laotian Government for a contract to run an operation like that of the Flying Tigers.”10 New York Times, Sept. 25, 1959, 4. Nine of the fliers were soon reported to be in Laos, including one active USAF officer (New York Times, Sept. 27, 1959, 16). Such authorization was necessary to avoid prosecution under Section 959 of the U.S. Criminal Code, which penalizes anyone who hires or retains another within the United States to enlist himself in any foreign military service.

Congress should ask for the publication of this secret order, to see what it authorized, whether Alsop’s misrepresentations were incorporated into it, how and by whom it was signed, and why it was dated on the day of Eisenhower’s seclusion in Scotland rather than awaiting his return to America three days later.

It is possible that talk of a high-level limited war conspiracy in Washington, perhaps even involving members of the present administration, is not as paranoid as writers like Schlesinger would have us think.

Pan Am and the Wall Street Overworld

One fact is certain: Joe Alsop, along with his Washington friend Tommy “the Cork” Corcoran, was in on the planning for an earlier secret Executive Order, that of April 15, 1941, which authorized Chennault’s American Volunteer Group or “Flying Tigers.”

Nor was Alsop the only link between the two Executive Orders: behind both was the shadowy presence of Pan Am, America’s largest airline in the Far East and a frequent “private” cover for U.S. military preparations before World War II.

In 1941 a former President of Pan Am’s Chinese subsidiary CNAC, William Pawley, was President of the “Central Aviation Manufacturing Company” which “hired” reserve officers as Flying Tigers pilots. In 1959 (as today) the former Pan Am Regional Director for the Middle East and India, George Arntzen Doole, was Chief Executive Officer of Air America, where he was assisted by two other former Pan Am Executives: Amos Hiatt, Air America’s Treasurer, and Hugh Grundy of CNAC, now President of Air America’s Taiwan operation Air Asia.

More specifically, the pilots for the “American Fliers for Laos” were recruited by a veteran USAF combat pilot, Clifford L. Speer. Speer was described as a “major in the Air Force Reserve and civilian employee at Fort Huachuca, Arizona11New York Times, Sept. 27, 1959, 16. where Pan Am has a contract to conduct highly secret “electronics weapons” research for the USAF.

Pan Am’s links with the Flying Tigers and CAT/Air America were both intimate and profitable, since Pan Am has always picked up a major share of the supporting charter airlift behind Chennault’s wartime and postwar operations. During the war, Pan Am’s huge Chinese subsidiary, China National Aviation Co. (CNAC), flew the bulk of what was then the world’s largest airlift “over the hump” into China, using many former pilots with the Flying Tigers.

Madame Chennault identifies Gordon Tweedy, a former lawyer with Sullivan and Cromwell who served from 1941 to 1948 with CNAC, as a leading member of Chennault’s “Washington Squadron,” the group organized by Corcoran and Alsop to mount lend-lease for China. Meanwhile, Marion Cooper, one of the many Pan Am directors who at one time or another have belonged to New York’s wealthy and exclusive Brook Club, flew out to China in 1942 to become chief of staff of what was by then Chennault’s China Air Task Force.

Thus paradoxically Chennault, a man born in Commerce, Texas, who was never popular with the hierarchies of the War and State Departments, had personal links to the Brook Club and to Pan Am, whose other directors in those days included a Vanderbilt, a Mellon, and two Whitneys.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Pan Am again supplied a trans-Pacific back-up to various CAT/Air America operations, starting with the Korean War. For example, it was on May 5, 1953, that Civil Air Transport, using planes and pilots “loaned” by the USAF, arrived in Hanoi to begin its airlift to Dienbienphu. Seventeen days later, on May 22, Pan Am began its “commercial service” to Hanoi, a service opened with the assistance of the U.S. government “in the national interest,” and a service which became a chief money-earner for Pan Am during the accelerated Vietnam War buildup.

The Wall Street interest in CAT, however, altogether transcended the profits to be reaped from military airlift contracts alone: CAT was the logistical backbone for the new post-Korean formula to stop Communism in Asia. As Eisenhower put it, “If there must be a war there, let it be Asians against Asians, with our support on the side of freedom.”

The world had been simpler before the war. As the U.S. Navy recorded then in its pamphlet, The United State Navy as an Industrial Asset — What the Navy Has Done for Industry and Commerce,

In the Asiatic area a force of gunboats is kept on constant patrol in the Yangtse River. These boats are able to patrol from the mouth of the river up nearly 2,000 miles into the very heart of China. American businessmen have freely stated that should the United States withdraw this patrol they would have to leave at the same time.

After World War II gunboat diplomacy was no longer respectable. Overt intervention was giving way to covert, just as the warship was being replaced by the airplane. In China, above all, there were numerous reasons why the United States wished to avoid too conspicuous an identification with the moribund regime of Chiang Kai-shek. Yet the demands of U.S. businessmen for protection in Asia were as great as ever.

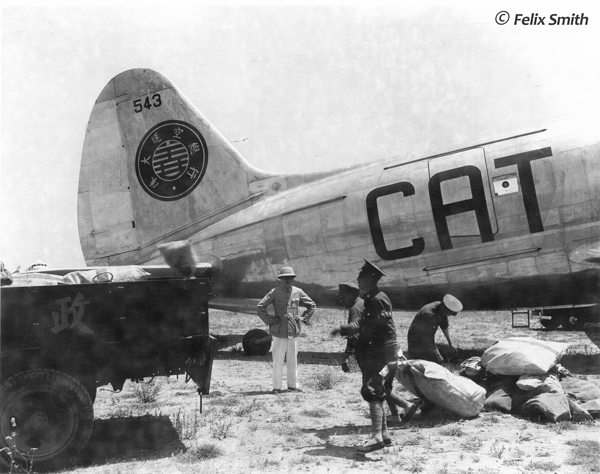

Civil Air Transport: A Corporate-State Amalgam

All of these factors must have influenced the decision of the U.S. State Department indirectly to subsidize General Chennault in the establishment of his post-war “private” Chinese airline, Civil Air Transport (at first called Chennault Air Transport). Kuomintang capital was undoubtedly involved as well, reportedly that of T.V. Soong and his sister Madame Chiang, and assuredly that of the Chinese industrialists Wang Yuan-ling, Hsu Kuo-mo, and Wang Wen-san (today’s CAT Chairman), then Manager of the Kincheng Bank which also invested in CAT.12 New York Times, Nov. 11, 1949, 14; Free China Review, Nov. 1953, 31. Air America pilots still repeat the rumor that “Madam Chiang owns the planes and we lease them from her” (San Francisco Chronicle, April 2, 1970, 31).

But CAT’s 47 U.S. Army Air Force transports were supplied by the U.S. relief agency UNRRA, for less than a tenth of their original cost, and for no cash. UNRRA gave Chennault contracts for Chennault and his men, including former OSS officers under Chennault such as Malcolm Rosholt

to fly relief supplies into the interior. When his bill for flying the supplies at high emergency rates equalled UNRRA’s low charge for the surplus planes, they became his.13Frillman and Peck, China: The Remembered Life, 288-89.

At first UNRRA Director LaGuardia turned down this proposal after he and all other responsible UNRRA officials opposed it as wasteful and unnecessary. However Laguardia “was called in for consultation by the State Department and told that both Soong and Madame Chiang had insisted on the need for the airline. Laguardia reversed himself.”14Wertenbaker, “The China Lobby,” Reporter, 9. The Kuomintang clearly wanted Chennault to stay on to support its widely scattered armies; and indeed when Chennault “got full support of the line, he used it in semi-military support of the Kuomintang.”15Peck, Two Kinds of Time.

Mail being loaded onto a CAT plane. Source: CAT Association

But the U.S. Government was also represented in CAT through Chennault’s partner Whiting Willauer, a graduate of Exeter, Princeton, and Harvard. Willauer had first been used as a trouble-shooter to fight Communists in the Criminal Division of the U.S. Justice Department in the 1930s (when he worked with Benjamin Mandel of the Dies-led HUAC Committee). He went on to help overthrow Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954 and to represent the State Department in the 1960 planning for the Bay of Pigs.

Willauer was until then a representative of the Foreign Economic Administration engaged in “economic intelligence” in the Far East. During the war, he had worked with Chennault as an employee of the Delaware corporation China Defense Supplies Inc., and as Special Assistant to its President, W.S. Youngman—the postwar partner of Tommy Corcoran. The Chairmen of China Defense Supplies had been T.V. Soong and Frederic Delano, uncle of Pan Am director Lyman Delano.

Another important member of CAT was its treasurer James J. Brennan, a wartime member of Chennault’s Washington squadron, who after the war became a personal secretary to T.V. Soong in China.

CAT in other words, like the Flying Tigers before it, represented a covert alliance between Soong KMT elements and key elements around Tommy Corcoran in the Democratic Administration. This “private” arrangement left Chennault free in 1948 and 1949 to lobby against the State Department in favor of greater aid and airlift to China—particularly to the Chinese Moslem armies of General Ma Pu-fang in the northwestern Qinghai Province which CAT was then supplying through Lanchow.

By 1949 Chennault’s views and activities were visibly much closer to Nationalist China’s than to the State Department’s. For example in November 1949, Chennault, shortly after a similar visit by Chiang, flew up to Syngman Rhee in Korea, “to give him a plan for the Korean military air force”; at this time it was still U.S. official policy to deny Rhee planes and to arm his men with light defensive weapons only, to remove any temptation to invade North Korea.16House Committee on Un-American Activities, International Communism: Consultation with Major General Claire Lee Chennault, 85th Cong., 2nd Sess., Apr. 23, 1958, 9-10; U.S. State Dept., U.S. Policy in the Korean Crisis, 1950, 21-22.

1949: US Governmental Involvement In CAT Grows

Yet, beginning in this same month of November 1949, covert U.S. government links with Chennault’s Chinese-backed airline began to be markedly increased. At first this new U.S. support was for ad hoc rather than long-term strategic purposes. The State Department feared that China’s civil air fleet, if it continued to serve under the new Chinese People’s Republic, would soon be used to mount an invasion against Taiwan.

Thus on November 30, 1949, on the day of the fall of Chungking, a dummy Delaware corporation, Civil Air Transport, Inc., was set up to “buy” over 70 planes of China’s two government airlines then taking refuge in Hong Kong; and thus deny them (by a process which Madame Chennault has since frankly called a “legal kidnapping”) to the newly constituted Chinese Peoples’ Republic.

The State Department could now exert pressure upon the Hong Kong and British authorities on behalf of “an American company”; and it did so energetically. Meanwhile, former OSS Chief William J. Donovan flew out to Hong Kong with Chennault’s old lawyer Tommy Corcoran, who was now CAT Counsel as well. The U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong (and its air force attache, Col. Leroy G. Heston, who had served with Chennault in China) played a particularly active role on CAT’s behalf.

One by-product of the deal was that Pan Am, unlike the other U.S. companies in China, secured compensation for its 20% investment in the airline CNAC. In fact, Civil Air Transport Inc.’s action in writing a check directly to Pan Am in New York, rather than to the CNAC offices in China, was one of the weakest links in its rather transparent case (or what Madam Chennault called “one last anti-Communist ‘miracle’”).17Congressional Record, Senate, Mar. 28, 1950, 4226.

As a mark of Wall Street’s control over the CIA in this period, one has only to note that, of the six civilian Deputy Directors named … between 1950 and 1952 … All of them were directly linked to the New York financial interests which profited not only from oil and other investments abroad but also from the new defense industries which were being developed for their protection.

Legally the new Delaware corporation, which supplied $4.8 million for the deal, issued only two of an authorized 2,000 shares — not to Chennault, but to former T.V. Soong employees Willauer and Brennan. It is possible that the $4.8 million really came from the CIA; for when the British Privy Council finally awarded the planes to Civil Air Transport, Inc. (overruling the Hong Kong courts), the seventy planes, which had been “bought” for a fraction of their real value, came home to the United States for repairs on the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier Windham Day.18Aviation Week, Feb. 2, 1953, 54.

But the legal work on the dummy corporation was handled by Tommy Corcoran’s law firm, whose business address was that reported over the next seven years by all of Civil Air Transport Inc.’s Washington directors: Tommy Corcoran, his law partner W.S. Youngman, whom Willauer had served as Special Assistant in China Defense Supplies, Corcoran’s brother Howard F. Corcoran, Duncan C. Lee who had flown out to China for OSS during the war,19Ironically, Duncan Lee, who was OSS Assistant General Counsel and before that in General Donovan’s Wall Street law firm, was denounced by Elizabeth Bentley as a Communist Party member and informer in the celebrated HUAC Hearings of 1948. Her testimony seems to have been intended to discredit in that election year not only the Democratic Administration, but also the OSS elements who were returning to it in the infant CIA (despite the bitter opposition of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover) and the so-called “liberal” or “Rockefeller” faction of the Republican Party (opposed by the Chicago or “Taft” faction, who for a while were able to help Hoover block the formation of the CIA). and Annetta M. Behan, the Notary Public who notarized the company’s annual reports filled out by herself.

Neither Corcoran nor the CIA seems to have done anything at this stage to help CAT solve its own financial and operating problems. In early 1950 Chennault had to advise his pilots that they would be put on half-pay, and were free to look for jobs elsewhere. The outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, saved CAT, which promptly began to fly the bulk of the U.S. military airlift inside Korea. On July 10 a second Delaware corporation was chartered: CAT Inc., later renamed Air America Inc. (the older Civil Air Transport Inc., having served its limited purpose of “kidnapping,” was quietly dissolved in 1956).

Control of the new corporation remained with the officers of the Chinese airline Civil Air Transport, who held four out of seven directorships. The remaining three went to the officer-directors of the holding company Airdale Corp., also chartered on July 10, 1950, allegedly as a pass-through for CIA funds. Airdale Corp. (in 1957 renamed Pacific Corp. has ever since held 100% of CAT Inc./Air America’s stock. With fresh capital, specially-recruited pilots, and its Korean charter contracts, CAT was soon prospering, possessing assets of some $5.5 million, and income in the order of some $6 to $12 million a year.20Colliers,Aug. 11, 1951, 35.

But CAT’s new American backing did nothing to change its status as the sole flag air carrier of Chiang’s Republic. On the contrary, from as early as October 1950, the Taiwan Foreign Ministry exchanged notes with various Asian countries to confirm the landing and loading rights of the burgeoning commercial airline CAT.

At some point in the 1950s, at the insistence of the Chiang Government, a 60% controlling interest in the commercial airline (CAT Co., Ltd., or CATCL, a Taiwan company) was granted or returned to the KMT interests who had originally invested in it. Thus, Wang Wen-san—previously Chairman of CAT’s Policy Board—replaced Chennault as Chairman of the CAT Board, a post he holds today. He was joined by Henry K. Yuan, a CAT employee, and by Y.C. Chen, apparently a former section chief in the KMT Ministry of Information and Director of the KMT’s Overseas Affairs Division.

A 40% interest was retained in the name of Airdale Corp., which in 1957 was renamed the Pacific Corporation. Legally speaking, CAT Inc./Air America Inc. (the Delaware corporation) and CATCL (the Taiwan company) are separate entities. In practice it is difficult to distinguish between Air America’s Taiwan subsidiary, Air Asia, and CATCL: the two operations shared directors, officers, facilities, pilots, and above all planes.

The CIA and “Plausible Deniability”

In the typical year 1963, for example, the World Aviation Directory attributed 4,600 employees and 300 pilots to CATCL at the same address. According to a former CATCL publicist, Air Asia “holds a service contract with CAT, which is the way the Americans operate the ‘Chinese-owned’ airline.”21Dibble, “The Nine Lives of CAT-II,” Saturday Review>, 50. CAT’s commercial “Mandarin Jet,” which crashed in 1968, was leased from the CIA-front “Southern Air Transport” in Miami, which flew in the Caribbean at the time of the Bay of Pigs and also worked with Air America in Laos and Vietnam.

Southern Air Transport’s attorney, Alex E. Carlson, also represented the Double-Chek Corporation (same address) which hired American pilots to fly at the Bay of Pigs.22Wise and Ross, The Invisible Government, 1965, 156. And Whiting Willauer, who in 1960 was the State Department’s senior representative on the Bay of Pigs Operation, later testified that CAT pilots trained the Cuban pilots involved.23U.S. Cong., Senate, Committee on the Judiciary, Communist Threat to the United States through the Caribbean, Hearings, July 27, 1962, 875.

Meanwhile, it would appear that in February-March 1952, the CIA ended the anomaly of its direct subsidy to a prospering commercial Taiwan airline. This was an outfit whose officers were lobbying against State Department policy in the hopes of overthrowing Mao. The airline seemed to have sold its financial interest in Airdale Corp. and CAT Inc. to a closely allied group of New York businessmen, of whom two (later three) were Joe Alsop’s club-mates in the Brook Club: Samuel Sloan Walker and William A. Read Jr., joined in 1958 by Robert Guestier Goelet. Walker, Read, and Goelet are still the controlling directors of Pacific Corp. and of Air America.24It is now clear that what I wrote in this and later paragraphs was wrong; and that indeed, as I speculated in the next paragraph, Walker, Read, and Goelet were merely providing a respectable front for a CIA proprietary. In 1975, when the CIA finally privatized its proprietary aviation assets, Air America, Air Asia, and Southern Air Transport were all sold off—the first two to the CIA-linked firm E-Systems. The reported information does however illustrate correctly how deeply embedded the early CIA was in the northeastern hereditary culture and milieu of the Brook Club and Wall Street.

It is possible of course that the data in the companies’ annual reports is misleading, that the Walker-Brook Club group is merely a front, and that the Airdale Corp. continued to be what is technically known as a “proprietary” directly owned by the CIA. But the support given by the CIA to Air America, such as the recruitment and security clearance of pilots from the military for covert operations, seems overall to reflect a contractual rather than a proprietary relationship, like the links between CIA and Lockheed in the development of the U-2 Program.25Air America pilots, like U-2 pilots, are mostly recruited from the USAF, and are said to have the same rights of return into the USAF at the end of their “civilian” tour.

In fronting for the CIA, Air America fronts even more significantly for the power which brought both agencies into being: the New York financial interests into whose milieu Air America’s controlling directors were born.

Air America, like CATCL, is clearly also engaged in private business for profit, and is said to make in the order of $10 million a year. According to the New York Times, it

flies prospectors looking for copper and geologists searching for oil in Indonesia, and provides pilots for commercial airlines such as Air Vietnam and Thai Airways and for China Airlines [Taiwan’s new Chinese-owned flag airline which since 1968 has taken over CAT’s passenger services].26New York Times, Apr. 5, 1970, 22.

It is the practice of the CIA to disengage itself from embarrassingly distasteful covert war enterprises it has helped to establish, such as Interarmco, the huge small-arms purchasing firm headed by former CIA agent Samuel Cummings (which imported inter alia the Mannlicher-Carcano said to have been used in the assassination of J.F. Kennedy).27Thayer, The War Business, 43-112.

In the case of CAT Inc., the divestment seems to have been handled by Walter Reid Wolf, the CIA’s Deputy Director for Administration between 1951 and 1953. Wolf was a trustee of the small Empire City Savings Bank in New York, of which Samuel Sloan Walker was Chairman and Arthur Berry Richardson, a third trustee. (A fourth trustee, Samuel Meek, was a director of Time, in those days strongly pro-Chiang, and later served on the CIA-front “Cuban Freedom Committee”).

In early 1952, Walker and Richardson became directors of Airdale (now Pacific Corp.) and CAT Inc. (now Air America) along with a third director, William A. Read, who was Walker’s wife’s former brother-in-law. Wolf was also a Vice-President of the National City Bank, and Senior Vice-President of its investment affiliate City Bank Farmers’ Trust, along with Walker’s cousin, Samuel Sloan Duryee. In addition, Wolf and Duryee sat on the American boards of Zurich Insurance and related Swiss companies. About the time that Wolf became CIA Deputy Director, Desmond FitzGerald, a member of Duryee’s law firm, joined the CIA and became for years in charge of its covert Indochina operations, working in conjunction with Air America. FitzGerald is said to have spent much of his time in Asia, yet he apparently never condescended to become a lowly CIA desk officer or station chief. Instead, his cover was that of a private lawyer with a downtown Washington address.

The Wall Street Dominance of the Early CIA

The 1952 Airdale changeover was, in short, a hand-over by Wall Street men inside the CIA to Wall Street men outside of it, a convenient arrangement in which the profits afforded the outside bankers probably counted for less than the non-accountability afforded the CIA.28As noted earlier, there was no such “hand-over.” As a mark of Wall Street’s control over the CIA in this period, one has only to note that, of the six civilian Deputy Directors known to have been named by CIA Director Walter Bedell Smith between 1950 and 1952, all six came from New York legal and financial circles; no less than five of them were (like wealthy inheritors Walker, Read, and Goelet) listed in New York’s restricted Social Register which indicated New York’s hereditary upper class. All of them, furthermore, were directly linked to the New York financial interests which profited not only from oil and other investments abroad but also from the new defense industries which were being developed for their protection.

Wolf, for example, was a Vice-President of National City Bank, the New York bank with the oldest and largest Oriental business (it had seventeen branches there before World War II). It was also, along with Chase Manhattan, perhaps the leading bank behind the aircraft industry in general and Pan Am in particular. (James Stillman Rockefeller has been since 1953 a director of both Pan Am and National City — which voted much of Pan Am’s stock in 1967).29Soon after he joined the board of CAT, Arthur Berry Richardson was named a member of Chase Manhattan’s Advisory Board. From 1955 to 1957 another CAT director was Harper Woodward (then an employee of Laurance Rockefeller) who represented the interests of the Rockefeller brothers (leading shareholders in Chase Manhattan) in various defense and CIA-linked industries.

The concentration of public power in restricted circles encourages collusion outside of formal channels, a tendency reinforced by the prevailing listlessness of public agencies; and when this collusion reaches such extremes as the reporting of patent falsehoods as facts … then this collusion may be said to be conspiratorial.

Behind the National City Bank stood its largest shareholder, the Giannini family’s Transamerica Corporation, whose more famous affiliate, the Bank of America was at the time opening up new branches in the Far East and participating actively in China Lobby activities. In 1948, for example, Tommy Corcoran’s law partner, D. Worth Clark, flew to China as part of a special lobbying mission with Russell Smith, a Bank of America vice-president, and former Time employee Edward B. Lockett, a ghost-writer for Chennault. Clark is said to have recalled later that the idea for the mission, which was paid for in part by the Nationalist Government, “popped up at a cocktail party at the Chinese Embassy.”30Koen, The China Lobby in American Politics, 108; Reporter, Apr. 15, 1952, 19. One director of Transamerica, James F. Cavagnaro, had already (through the World Commerce Corporation) been involved in one illegal private war enterprise in support of Chiang (Commerce International China, or CIC).31See Introduction.

Parapolitics, the Brook Club, and the Milieu of Inheritance

In other words it is misleading to describe Samuel Walker’s Air America as (in the words of the New York Times) “the Central Intelligence Agency’s private air subsidiary.”32 New York Times, June 13, 1966, 4.

In fronting for the CIA, Air America fronts even more significantly for the power which brought both agencies into being: the New York financial interests into whose milieu Air America’s controlling directors were born. Thus it is no accident that Walker, Read, and Goelet are all inheritors, wholly respectable but otherwise undistinguished, of significant nineteenth-century fortunes; and thus more “reliable” than self-made entrepreneurs.33 In 2022, I would now talk here of the milieu established by this background, adding that “milieu” is a better term than “network” or “structure” to describe the indefinable connections that made for the continuing influence of New York inherited wealth in the Vietnam war era..

Walker’s uncles and first cousins, for example, included directors at one time or another of Chase National (Gordon Auchincloss), National City (Samuel Sloan), City Bank Farmers’ Trust (Samuel Sloan Duryee), Bankers Trust and Pan Am (Samuel Sloan Colt): other cousins are married to a du Pont, a Tiffany, two Milburns, and William Bundy’s sister.

Thus the creation of Air America, like that of the CIA itself, is an exercise in what I have elsewhere called parapolitics — the generation of political results for which accountability is consciously diminished. Parapolitics has been Wall Street’s preferred mode of foreign intervention since World War II. Gunboats are no longer used to overthrow foreign governments which threaten the nationalization of oil companies, but until recently (with rare exceptions such as Cuba) gunboats have not been needed. “Private” arrangements, with or without CIA backing, have usually sufficed to do the job.

The first example of CIA parapolitics, in 1948, is a paradigm illustrating the true relationship between “private” and “public” power (the Brook Club and the White House) then prevailing in America. Truman has since told us that “I never had any thought … when I set up the CIA that it would be injected into peacetime cloak-and-dagger operations.”34Washington Post, Dec. 22, 1963; quoted in Hilsman, 63.

His intentions, unfortunately, counted for less than those of Allen Dulles, then a New York corporation lawyer and President of the Council on Foreign Relations. The Administration became concerned that the Communists might shortly win the Italian elections:

Forrestal felt that a secret counteraction was vital, but his initial assessment was that the Italian operation would have to be private. The wealthy industrialists in Milan were hesitant to provide the money, fearing reprisals if the Communists won, and so that hat was passed at the Brook Club in New York. But Allen Dulles felt the problem could not be handled effectively in private hands. He urged strongly that the government establish a covert organization with unvouchered funds, the decision was made to create it under the National Security Council.35Wise and Ross, The Espionage Establishment, 166.

This fateful essay in non-accountability is instructive: the Defense Secretary felt the operation should be private, but a Wall Street lawyer determined it should be public. By this arrangement, presumably, the men in the Brook Club even got their money back; since then the funds (unvouchered) have been ours.

It is interesting now to consider Alsop’s phony “invasion” of 1959 from the perspective, not of Laos, but of New York’s Brook Club, which Cleveland Amory described in Who Killed Society as “perhaps clubdom’s richest from the point of view of inherited wealth.” The club has only some 400 members in all, of whom only a handful condescend to become “in-and-outers” in temporary government service, or even to join the Rockefeller-sponsored but more elite-oriented Council on Foreign Relations.36Though my figures undoubtedly fall short of the true count, I have located only two Brook Club members in high government office during the 1950s, Undersecretary of State David K.E. Bruce (1952), and Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Walter S. Robertson (1953-59). Out of a total Council on Foreign Relations membership of 1383 in 1960-61, I have found eleven from the Brook Club: Norman Armour, Robert Woods Bliss, David K.E. Bruce (who married a Mellon), James Bruce, W.A.M. Burden, Henry S. Morgan, Grayson M.P. Murphy, William H. Osborn (a Dodge heir), Paul G. Pennoyer (Morgan’s brother-in-law), Warren Lee Pierson, and Robert Strausz-Hupé. The information in the New York Social Register alone shows at least 57 CFR members from the Rockefeller brothers’ University Club.

Yet the Brook Club was well-represented in the background of Alsop’s “invasion.” Joe Alsop himself was a member of the Brook Club, as were two directors of Pan Am and three of the five directors of the Pacific Corporation, whose subsidiary, Air America, began in 1959 to violate Laotian neutrality (and the U.S. neutrality laws) more and more openly.

Air America worked closely with the CIA in this period. For many years the CIA operation in Laos had been controlled by Brook Club member Desmond Fitzgerald, a former liaison officer with the Nationalist Chinese New Sixth Army who in 1951 went into the CIA from the law firm of Samuel Sloan Walker’s cousin, Samuel Sloan Duryee. (Another former member of Duryee’s firm was Harper Woodward, a director of the Taiwan commercial airline Civil Air Transport from 1955 to 1957 as an employee representing the interests of Laurance Rockefeller — the only Rockefeller to belong to the Brook Club.)

And while Brook Club member Walter S. Robertson, for six years a leading friend of Chiang Kai-shek as Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, had just resigned (as of July 1, 1959) for reasons of illness, his place had been taken by his good friend James Graham Parsons, another New York socialite who had served for years as the personal secretary of Brook Club member and former Ambassador Joseph Grew (the cousin of J.P. Morgan). Grew had been best man at Parsons’ wedding in 1936, when one of the ushers was Winthrop Brown of the Brown Brothers Harriman family (major investors in Pan Am), who became Ambassador to Laos in 1960.

Finally, in 1959 the leading proponent of what he called “A Forward Strategy for America” in Asia — confronting China at its very borders — was Viennese-born Brook Club member Robert Strausz-Hupé, a former New York investment banker married to [Eleanor DeGraff Cuyler Walker], the first wife of Samuel Sloan Walker’s brother Joseph. Robert Strausz-Hupé’s Foreign Policy Research Institute, financed in part by CIA funds, was then in the forefront of a highly-organized campaign by right-wing military and business circles against the more limited policy of merely “containing” communism. In Strausz- Hupé’s words, containment “allows the communists to devote full time to the job of aggression … defensive measures themselves can never assure victory.”37Strausz-Hupé, A Forward Strategy for America, 28.

The “China Lobby” and the Revolving Door to the Right-Wing Overworld

These facts do not suggest a clubroom or genealogical conspiracy. They are symptomatic of a common right-wing milieu, not narrowly restricted to the Brook Club, whose members no doubt differed in their opinions as much as other human beings, but who collectively exercised far greater influence — because of their participation in this privileged milieu — than the “private” status of some individuals might indicate.

The reality of this milieu helps us to understand the alleged uncontrollability in Laos of what Schlesinger called “CIA man in the field” Desmond Fitzgerald. Desmond Fitzgerald was assuredly in as good a position to influence U.S. policy as U.S. policy was to influence Desmond Fitzgerald. (Nor was such influence confined to Laos — for example, it is recorded that in 1960, John F. Kennedy, two days before his nomination, received Joe Alsop and his publisher Phil Graham, and agreed to their arguments that he should accept Tommy Corcoran’s old protege Lyndon Johnson as his running mate.)38Steinberg, Sam Johnson’s Boy, 528.

The reality of this milieu helps us to understand the alleged uncontrollability in Laos of what Schlesinger called “CIA man in the field” Desmond Fitzgerald. Desmond Fitzgerald was assuredly in as good a position to influence U.S. policy as U.S. policy was to influence Desmond Fitzgerald. Such influence was not confined to Laos. For example, it is recorded that in 1960, John F. Kennedy, two days before his nomination, received Joe Alsop and his publisher Phil Graham, and agreed to their arguments that he should accept Tommy Corcoran’s old protege Lyndon Johnson as his running mate.39Steinberg, Sam Johnson’s Boy, 528.

The existence of a milieu is not in itself culpable, nor is the neutral consequence that men who possess influence will seek to use it. But the concentration of public power in restricted circles encourages collusion outside of formal channels and review, a tendency reinforced by the prevailing listlessness of public agencies; and when this collusion reaches such extremes as the reporting of patent falsehoods as facts or the timing of submissions so as to preclude review, then this collusion may be said to be conspiratorial.

What is especially culpable in the present instance is that Air America—the instrument selected for covert intervention in Laos—was not even securely American. Despite its name and the recorded legal facts of its ownership, the capital, plant, officers, and pilots of the Air America operation were in large part Taiwanese.

That both Brook Club members and the Kuomintang should be behind a CIA-linked airline may be surprising to some. But there are many instances of active collaboration between New York wealth and the KMT. For example, Brook Club member Richard C. Patterson, a former Ambassador to Guatemala who founded the China-American (later the Far East-American) Council of Commerce and Industry, was also a director (along with Brook Club member Warren Lee Pierson) of the Nationalist Chinese Li family’s Wah Chang Corporation, a prominent U.S. tungsten firm with Chinese shareholders. Wah Chang had long enjoyed special political favors from Lyndon Johnson and owned an important trading subsidiary, the Tai Wah Trading Company, in Thailand. (Patterson, incidentally, was also a director of another firm, the successful conglomerate City Investing Co., with Air America director Robert G. Goelet.)

Vice President Nixon meets with Chiang Kai-shek in 1956. Source: Allen, “On Safari”

Joe Alsop’s own brother-in-law, Percy Chubb II (whose family insurance firm did business in Cuba and the Philippines) became Board Chairman of the newly-incorporated Cathay Insurance Company in 1947, most of whose capital was KMT money in flight from China. One of Chubb’s fellow directors was K.P. Chen (Chen Kuo-fu), a relative of Chiang, a key figure in the KMT “CC clique” who was a director of the Bank of China along with Madame Chiang’’s brother T.V. Soong and her brother-in-law H.H. Kung. (A fourth director was Reignson Chen from the Wah Chang Trading Corp. and China Defense Supplies). From their residences in New York, K.P. Chen, Soong, and the Kungs were at this time channeling funds into domestic U.S. “China Lobby” activities, such as financial support for Richard Nixon’s Senate campaign of 1950.40Koen, The China Lobby in American Politics, 42; Reporter, April 15, 1952, 20.

Such financial collaboration between the KMT and Wall Street was paralleled by another that was ideological. Archibald Roosevelt, a cousin of Joe Alsop’s, joined the “social circle” (better known as the “China Lobby”) of Alfred Kohlberg, H.H. Kung, and Archbishop Paul Yu-pin, at about the time his nephew Quentin Roosevelt of OSS succeeded Gordon Tweedy in China as a director of CNAC.41Others in this social circle ranged from Senator McCarthy, Walter Judd, William F. Buckley, and Louis Budenz, to Representative Clare Booth Luce, and Roy Howard, later a director of Pan Am.

In the same period, three members of the Pan Am lobby in Congress became key figures in the emerging “China Lobby” in Washington: Senator McCarran (who had first become famous as the author of the 1938 Civil Aeronautics Act), Senator Brewster (the so-called “Senator from Pan Am”) and Clare Booth Luce, whose husband Henry Luce was not only a leading publicist for Chiang but an old Yale schoolmate and Connecticut neighbor of Pan Am President Trippe.

In 1957 the pro-Chiang lobby in America was quietly but effectively re-organized as the American-Asian (later American Afro-Asian) Educational Exchange, Inc., with Marvin Liebman as Secretary-General and Brook Club member Joseph Grew as Chairman. By 1959 Grew had been succeeded as Chairman by Brook Club member Charles Edison (son of Thomas Alva Edison), a former Vice-Chairman with General Donovan of the Committee to Defend America by Aiding Anti-Communist China.42Edison (along with three members of the Kohlberg circle) was also one of the eight members of the American Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, a group supporting the emigre NTS and ABN groups in West Germany. Among the AAEE’s 58 members were members of the old Kohlberg circle (including Mrs. Kohlberg) and the newer “American Friends of Vietnam” (Christopher Emmet) as well as the editor of the New Leader(Sol Levitas) and at least one publicist for the John Birch Society (George S. Schuyler).43For a complete list as of 1960 see Labin, The Unrelenting War.

The Exchange’s name and avowed purpose (“the exchange of information, literature, and personnel for the purposes of creating a broader understanding”) were deceptive: in practice, the Exchange was used to channel Taiwanese funds for the publication of pro-Chiang propaganda in the New Leader and elsewhere.44See Labin, The Unrelenting War. Meanwhile its Chairman and Secretary-General, Charles Edison and Marvin Liebman, also served as Chairman and Secretary-General of a secret Steering Committee, wholly unpublicized in this country, to erect Chiang Kai-shek’s Asian Peoples’ Anti-Communist League (APACL), in alliance with East European emigres and right-wing industrialists from Europe and Latin America, into a World Anti-Communist League.45Asian Peoples’ Anti-Communist League, APACL — Its Growth and Outlook. The Deputy Secretary-General of this secret United States committee was Francis J. McNamara, who by 1963 was staff director of the House Un-American Activities Committee. The “Asian Advisory Board” of the AAEE, which included the globe-trotting APACL organizer Ku Cheng-Kang, was in fact composed almost exclusively of APACL delegates and associates.

Edison’s and Liebman’s efforts were concerned with those in Europe of the International Committee for Information and Social Activities (CIAS): the CIAS President, Fritz Cramer, had been a German counter-intelligence officer during World War II, and its Secretary-General, Alfred Gielen, had before the war written anti-Semitic propaganda for Hitler’s Anti-Comintern under the imprint of a swastika.46Gielen, Das Rotbuch ueber Spanien. Another associate of the APACL and CIAS was Gen. Ferenc Farkas, chief military advisor to the ABN, who led the Hungarian “Arrow Cross” troops of quisling Ferenc Szalasi (executed after the war) with the Nazis against the Russians. The WACL, which can in effect be called the Second Anti-Comintern, was in fact established in Taipeh on September 7, 1967 — another event not publicized in this country.

Personnel of the AAEE and APACL appear to have played a role along with CAT in the phony Laos “invasion” conspiracy of 1959 — notably Ku Cheng-kang, who was also a KMT Central Committee member of the Chiang Ching-kuo faction, and a former Minister of the Interior. (He is now a member of the KMT Central Standing Committee, or Politburo). One has to recall that early 1959 was the time of the great Tibetan uprising, an uprising supported by a covert airlift from Taiwan. This uprising involved not only Tibetans but other ethnic minorities to the east in the contiguous provinces of Qinghai, Sikang, and Yunnan, which during the 1945-49 war had been supported by Chennault and CAT.

Personnel of the AAEE and APACL appear to have played a role along with CAT in the phony Laos “invasion” conspiracy of 1959 — notably Ku Cheng-kang, who was also a KMT Central Committee member of the Chiang Ching-kuo faction, and a former Minister of the Interior. (He is now a member of the KMT Central Standing Committee, or Politburo). One has to recall that early 1959 was the time of the great Tibetan uprising, an uprising supported by a covert airlift from Taiwan. This uprising involved not only Tibetans but other ethnic minorities to the east in the contiguous provinces of Qinghai, Sikang, and Yunnan, which during the 1945-49 war had been supported by Chennault and CAT.

By March 1959, according to Bernard Fall, “Some of the Nationalist guerrillas operating in the Shan states of neighboring Burma had crossed into Laotian territory and were being supplied by an airlift of ‘unknown planes.’”47Fall, Anatomy of a Crisis, 99. As was revealed in 1961 when one of CAT’s planes from Taiwan was shot down by the Burmese Air Force, these guerrillas were supported by the Free China Relief Association (FCRA), a member group of the Taiwan APACL with the same address and personnel.48New York Times, Feb. 16, 1961, 9; Singapore Straits-Times, Feb. 20, 1961, 1.

In May and June of 1959, FCRA Secretary-General Fang Chih, another member of the KMT and APACL, visited KMT camps in Laos, Burma, and Thailand, as he did again in 1960. On August 18, 1959, five days before the arrival of two CAT planes in Vientiane, and twelve days before Alsop’s “invasion,” Ku Cheng-kang, who was President of the FCRA as well as of the Taiwan APACL, visited Vientiane and saw the mysterious but influential Col. Oudone Sananikone, a member of what was then the ruling Laotian family, and nephew of the Laotian Premier Phoui Sananikone.49APACL, Free China and Asia, 14. On August 26, 1959, in Washington, James Graham Parsons signed with Oudone’s father, Ngon Sananikone, an emergency aid agreement that would pay to charter the CAT planes. This was only a few hours after Eisenhower had left for Europe on the same day, not having had time to study the aid request, for Ngon had only submitted it on August 25.

A New Bay of Pigs, and the Proto-Grand Chessboard

Oudone Sananikone headed a “Laotian” paramilitary airline, Veha Akhat, which in those days serviced the opium-growing areas north of the Plaine des Jarres. CAT had not yet begun its operations to the Meos [Hmong] in this region, which offered such profitable opportunities for smuggling as a sideline for enterprising pilots.50For a recent report linking Air America and the CIA to opium-smuggling in Laos, see the Christian Science Monitor, June 16, 1970, 8. “The Lao Army is deeply involved in the lucrative opium business, and Laotian Air Force planes transport opium. Some private planes say the Air Force’s opium runs are made with CIA ‘protection.'” In fact, Veha Akhat was little more than a front for the Nationalist Chinese airlines from which it chartered six planes and pilots. On February 19, 1961, four days after the CAT/FCRA plane was shot down by the Burmese, a Veha Akhat C-47 leased from a Taiwan company was shot down over Laos; four of the six personnel aboard were said to be Nationalist Chinese officers.51Cf. Bangkok Post, Feb. 22, 1961, 1; Singapore Straits Times, Feb. 22, 1961, 3. The same year Taiwan’s second airline, Foshing, reported a decrease in its air fleet from three C-47’s to two. Foshing Airlines was headed by Moon Chin, a former Assistant Operating Manager of CNAC under William Pawley. Colonel Oudone Sananikone also figured prominently in the secret three-way talks between officers of Laos, South Vietnam, and Taiwan, which preceded the Vientiane coup and the resulting crisis of April 19, 1964 — a coup which was reported two days in advance by Taiwan Radio.52Bangkok Post, Apr. 18, 1964.

US Air Force planes used to train Laotian, Thai, and CIA pilots. Source: US Air Force